Jurassic Fish Choked on Squid-Like Belemnites, Study Finds

A recent study by Dr. Martin Ebert and Dr. Martina Kölbl-Ebert revealed that Tharsis fish from the late Jurassic period choked to death after swallowing belemnites, squid-like cephalopods. The fossils were found in the Solnhofen Archipelago, known for its well-preserved marine deposits. The fish, primarily micro-carnivores, mistook the belemnites for food due to algae growth on their bodies. Unable to swallow the belemnites completely, the fish ultimately suffocated. This discovery sheds light on the feeding habits of these ancient creatures.

A study by Dr. Martin Ebert and Dr. Martina Kölbl-Ebert examined the remains of some 4,200 Tharsis fossil specimens. They found that some of these fish, all of which were subadults, would occasionally attempt to or accidentally swallow belemnites (squid-like cephalopods), leading to the Tharsis choking to death.

The work is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

The Tharsis fish is an extinct genus of late Jurassic fish which is commonly found in the marine fossil deposits of the Solenhofen Plattenkalk (Solenhofen Limestone).

The Eichstätt-Solnhofen basins are known for their exceptionally well-preserved fossil remains, including crabs, ammonites, sea lilies, jellyfish, and famously, Archaeopteryx.

During the Late Jurassic, the Eichstätt-Solnhofen basins formed part of the Solnhofen archipelago, which was characterized by high salinity and low oxygen levels, providing unfavorable conditions for life.

The lagoon floors were especially hostile environments, resulting in the complete absence of any living organisms.

Yet it is in these fine sediments that fossil remains of Tharsis are commonly found, and provided the basis of Dr. Ebert and Dr. Kölbl-Ebert's study.

\"Tharsis is the second most common genus in the Solnhofen Archipelago with some 4,200 specimens that Martin Ebert, the first author of the paper, has actually seen in various collections,\" explains Dr. Kölbl-Ebert.

A far less common, but occasionally found fossil is that of belemnites. In the Plattenkalk basin, only around 120 belemnites have been found, making them rather rare compared to fish finds, which number in the 15,000s.

Belemnites were Jurassic and Cretaceous cephalopods that typically favored life in the open sea and were among the first to disappear in low-oxygen environments.

Many of the fossil belemnites found in the Plattenkalk basins are overgrown with bivalves, indicating they had been dead for some time, likely floating on the water's surface before being washed into the Solnhofen Archipelago, where they sank to the bottom.

The only known large fish to prey on belemnites are sharks. However, during their examination of the Tharsis fossils, the researchers noted that some Tharsis had attempted to swallow belemnites.

Despite these fossils being well known, this phenomenon had previously been left undocumented. According to Dr. Kölbl-Ebert, this may in part be due to the sheer number of Tharsis fossils, of which only a rare few are of interest to most researchers.

\"Since Tharsis is so very common, taxonomists usually look only at a very few, exceptionally well-preserved specimens. Martin looks at so many specimens, because he is also doing statistics and is interested in ecology as well,\" Dr. Kölbl-Ebert explained.

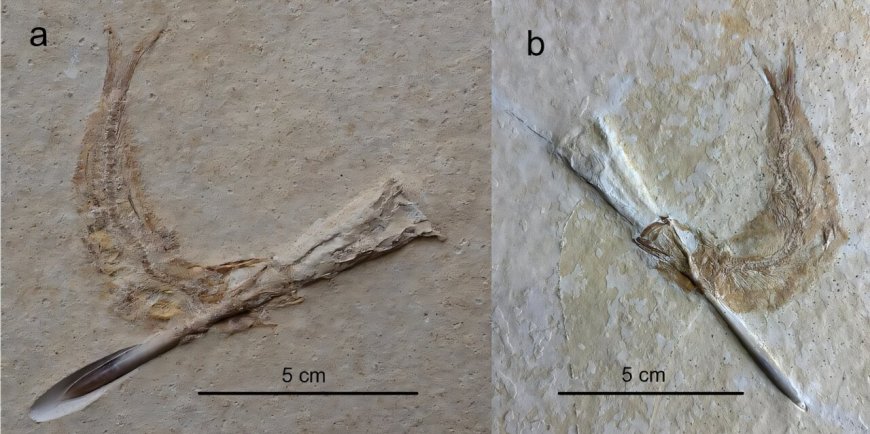

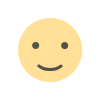

These Tharsis specimens were found to have belemnites lodged in their throats. It is known that Tharsis were micro-carnivores or visual zooplanktivores. It is assumed that they were in the habit of sucking remnants of decaying dead tissue, algae, or bacterial growth from floating objects.

Since the belemnites were likely already dead for a while by the time the Tharsis got to them, it is possible they had some algae growth on their bodies.

This could have allowed them to be mistakenly identified as food by the Tharsis, explains Dr. Kölbl-Ebert. \"We assume from present-day experience that such floating objects are quickly overgrown with algae and bacteria, thus for the fish they smell and taste like food.\"

While the tip of the belemnite's rostrum would fit in a Tharsis' mouth, the bullet-shaped belemnite would increase in diameter, leading to the fish eventually being unable to swallow it any further.

As the Tharsis was unable to spit out or bite off the belemnite, all specimens instead attempted to expel the belemnites through the gills.

Death would have followed quickly. From modern observations of fish with large prey stuck in their throats, it is known that, within a few hours, insufficient oxygen would have led to suffocation.

Written for you by our author Sandee Oster, edited by Sadie Harley, and fact-checked and reviewed by Robert Egan—this article is the result of careful human work. We rely on readers like you to keep independent science journalism alive. If this reporting matters to you, please consider a donation (especially monthly). You'll get an ad-free account as a thank-you.

More information: Ebert, M., Kölbl-Ebert, M. Jurassic fish choking on floating belemnites. Scientific Reports (2025). doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00163-7 Journal information: Scientific Reports

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0