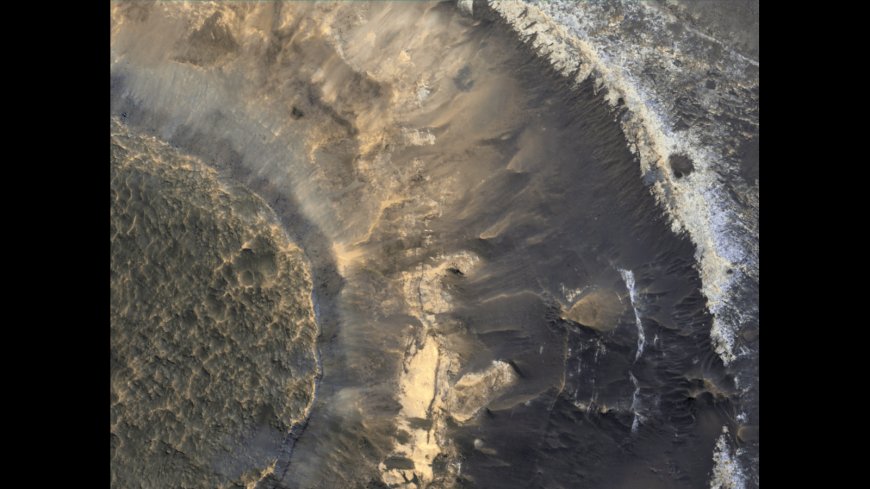

Could Mars have once supported life in its clay layers?

A recent study suggests that Mars may have had environments suitable for life in its thick clay deposits. These clay layers formed around 3.7 billion years ago under warmer and wetter conditions. The stable terrain on Mars could have sustained habitable conditions for extended periods. The study analyzed 150 clay deposits near ancient lakes and found that chemical weathering played a crucial role in preserving the clays over time.

The thick, mineral-rich layers of clay found on Mars suggest that the Red Planet harbored potentially life-hosting environments for long stretches in the ancient past, a new study suggests.

Clays need liquid water to form. These layers are hundreds of feet thick and are thought to have formed roughly 3.7 billion years ago, under warmer and wetter conditions than currently prevail on Mars.

\"These areas have a lot of water but not a lot of topographic uplift, so they're very stable,\" study co-author Rhianna Moore, who conducted the research as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas' Jackson School of Geosciences, said in a statement.

\"If you have stable terrain, you're not messing up your potentially habitable environments,\" Moore added. \"Favorable conditions might be able to be sustained for longer periods of time.\"

On our home planet, such deposits form under specific landscape and climatic conditions.

\"On Earth, the places where we tend to see the thickest clay mineral sequences are in humid environments, and those with minimal physical erosion that can strip away newly created weathering products,\" said co-author Tim Goudge, an assistant professor at the Jackson School's Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

However, it remains unclear how Mars' local and global topography, along with its past climate activity, influenced surface weathering and the formation of clay layers.

Using data and images from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter — the second-longest-operating spacecraft around Mars, after the agency's 2001 Mars Odyssey — Moore, Goudge, and their colleagues studied 150 clay deposits, looking at their shapes and locations, and how close they are to other features like ancient lakes or rivers.

They found that the clays are mostly located in low areas near ancient lakes, but not close to valleys where water once flowed strongly. This mix of gentle chemical changes and less intense physical erosion helped the clays stay preserved over time.

\"Clay mineral-bearing stratigraphies tend to occur in areas where chemical weathering was favoured over physical erosion, farther from valley network activity and nearer standing bodies of water,\" the team wrote in the new study, which was published in the journal Nature Astronomy on June 16.

The findings suggest that intense chemical weathering on Mars may have disrupted the usual balance between weathering and climate.

On Earth, where tectonic activity constantly exposes fresh rock to the atmosphere, carbonate minerals like limestone form when rock reacts with water and carbon dioxide (CO2). This process helps remove CO2 from the air, storing it in solid form and helping regulate the climate over long periods.

On Mars, tectonic activity is non-existent, leading to a lack of carbonate minerals and minimal removal of CO2 from the planet's thin atmosphere. As a result, CO2 released by Martian volcanoes long ago likely stayed in the atmosphere longer, making the planet warmer and wetter in the past — conditions the team believes may have encouraged the clay's formation.

The researchers also speculate that the clay could have absorbed water and trapped chemical byproducts like cations, preventing them from spreading and reacting with the surrounding rock to form carbonates that remain trapped and unable to leech into the surrounding environment.

\"The clay is probably one of many factors that's contributing to this weird lack of predicted carbonates on Mars,\" said Moore.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0