Simple Blood Test Shows Promise in Detecting Heart Transplant Rejection Early

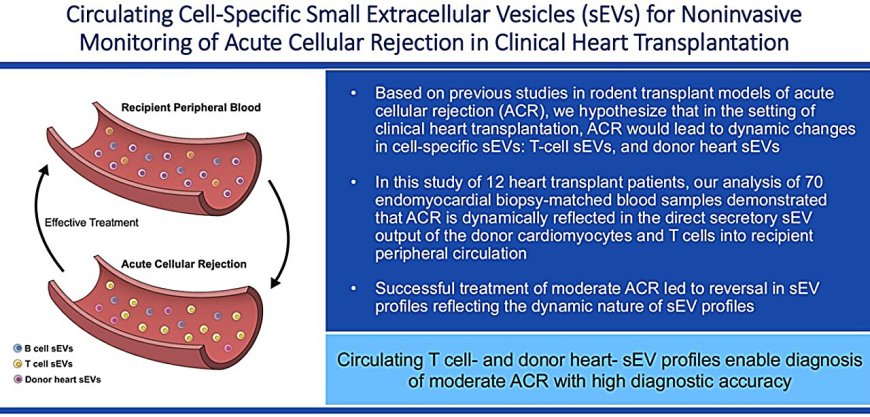

A recent study reveals the potential of using a biomarker found in exosomes to detect heart transplant rejection without the need for invasive biopsies. The study, published in Transplantation, marks a significant advancement in monitoring rejection in heart transplant patients.

Following a heart transplant, patients must undergo surgical biopsies so that clinicians can monitor for signs of organ rejection. A new study shows the promise of a biomarker that could allow doctors to replace these invasive biopsies with a simple blood test. The results are published in the journal Transplantation.

To communicate with one another, cells release exosomes—little biological packets containing various molecules that transfer information to other cells. Over the last decade, Yale School of Medicine (YSM) researchers have been studying the potential of exosomes to serve as a biomarker for heart transplant rejection in animal models.

The new study in heart transplant patients is a leap forward in translating these concepts in animal studies to heart transplant patients, bringing new biomarker testing from the laboratory into the clinical setting.

\"Our patients have few options for surveillance for rejection,\" says study co-author Sounok Sen, MD, medical director of the Yale Cardiac Transplantation and Mechanical Circulatory Support Program and assistant professor of medicine (cardiology) at YSM. \"The gold standard has always been a heart biopsy, but we always wondered if there were better ways to do this that didn't require invasive procedures.\"

The study was led by principal investigator Prashanth Vallabhajosyula, MD, associate professor of surgery (cardiac), along with Sen and first author Laxminarayana Korutla, Ph.D., a research scientist at YSM.

\"For the past 50-plus years, ever since we started doing heart transplants, there has been a drive to replace repeated heart biopsies because it's not practical to keep doing invasive biopsy procedure after procedure,\" says Vallabhajosyula. \"Having a noninvasive molecular window into what the cells of interest are doing with regards to the transplanted organ is critical.\"

Organ rejection associated with heart and T cell exosome changes

Rejection occurs when the patient's own immune system recognizes a transplanted organ as foreign and mounts an immune response against it. The most common kind of rejection is known as acute cellular rejection, which is mediated by a type of immune cell known as T cells.

\"T cells are constantly surveilling their environment, looking for infections and other things that are 'non-self,'\" Vallabhajosyula explains. \"They see the transplanted heart as non-self, so they mount an attack.\"

Clinicians grade acute cellular rejection as mild, moderate, or severe. Mild rejection is often asymptomatic, though some patients may experience subtle, flu-like symptoms. In moderate or severe cases, symptoms may include fast or irregular heartbeat, drop in blood pressure, dizziness, and shortness of breath.

Using a tissue biopsy, pathologists can look for signs of rejection such as the presence of T cells and assign a grade based on the severity of the extent of injury the T cells cause to the transplanted heart.

This grading helps guide treatment decisions. Treatment for moderate or severe acute cellular rejection includes increasing immunosuppressive medications to reverse rejection, while mild cases often just require careful monitoring of the patient.

For the study, the researchers took blood samples from 12 heart transplant patients before and after surgery and examined the molecular cargo inside exosomes released by T cells, another type of immune cell called B cells, and the donor heart. Six of these patients cumulatively experienced 11 moderate acute cellular rejection episodes.

When the donor heart was not being rejected by T cells, the researchers found specific quantities of diverse molecular cargo contained by the exosomes from the heart and T cells. But when the heart was undergoing rejection, they saw an increase in certain markers associated with the rejection process.

Importantly, one study participant developed a different type of organ rejection called antibody-mediated rejection, which is mediated primarily by B cells with the help of T cells. By looking inside exosomes from the patient's B cells, the researchers were able to detect this type of rejection as well.

Because the therapies for acute cellular and antibody-mediated rejection are different, having a test that can detect and distinguish between the types of transplant rejection could be a useful tool for assisting clinicians in determining a treatment plan.

\"This is the first time that we've had a noninvasive method to delineate between the different types of rejection that may occur within the heart,\" Sen says. The team is further studying this capability of their new test in ongoing research.

New test detects early organ rejection and treatment efficacy

Over the last few decades, researchers have explored other biomarkers to replace surgical biopsies. Most cases of acute cellular rejection happen within the first six months following the transplantation procedure. However, the few blood tests that are commercially available are ineffective at detecting rejection within the first 30 days after the transplant.

In the current study, 10 out of the 11 rejection episodes happened within the first 38 days post-transplant and the researchers successfully detected them all. \"With the platform that we designed, we did not have any time limits,\" Vallabhajosyula says. \"We can now start looking for rejection from the very beginning.\"

Furthermore, when a surgical biopsy detects moderate or severe rejection, clinicians need to treat it by increasing the patient's immunosuppressive medications. But currently, there is no good way to noninvasively confirm if the treatment is working. \"Sometimes, patients end up getting three, four, five biopsies after we've detected rejection,\" says Vallabhajosyula.

When patients in the current study were treated for rejection, the researchers observed that the exosome profiles of the T cells and donor heart cells reverted back toward baseline. \"Not only can we detect rejection, but our investigation also suggests that we can use our exosome platform to potentially monitor the efficacy of treatment of rejection,\" Vallabhajosyula says.

Improving the lives of heart transplant patients

Now, the YSM team is analyzing biopsy samples from more than 100 patients. With this larger cohort, they are collecting more data on their platform's ability to test for different kinds of rejection, like antibody-mediated rejection. \"There are exciting opportunities to see the full potential of this type of analysis to help transplant patients in the future,\" says Sen.

Today, taking biopsies of the heart remains the gold standard for detecting transplant rejection, but it is not without its risks. For example, Vallabhajosyula recalls a patient on whom he had performed a heart transplant. The transplant surgery was successful, but after a routine heart biopsy seven days post-operation, the patient suffered a problem with her tricuspid valve that caused renal failure. Vallabhajosyula had to perform additional surgery to fix the injury.

Having a less invasive way to monitor an individual's immune response would be life-changing for recipients of transplanted organs, the Yale team says. \"As a physician, when you go through experiences like that with your patient, you never forget it,\" Vallabhajosyula says. \"If science like this can potentially help avoid such situations for our patients, what more could I ask for as a physician?\"

Vallabhajosyula says this work wouldn't have been possible without the collaboration between his supportive laboratory staff, Sen and the Heart Failure Program, the heart failure program at the University of Pennsylvania, and Korutla's expertise.

More information: Laxminarayana Korutla et al, Circulating Tissue Specific Extracellular Vesicles for Noninvasive Monitoring of Acute Cellular Rejection in Clinical Heart Transplantation, Transplantation (2025). DOI: 10.1097/TP.0000000000005369

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0